Sudan’s army-backed government has accused Kenya of acting as a conduit for weapons supplied by the United Arab Emirates (UAE) to the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a group locked in a brutal conflict with Sudan’s regular army since April 2023.

This accusation, announced on Tuesday, has cast a shadow over relations between Sudan and Kenya, while drawing fresh attention to the web of foreign involvement fuelling a war that has already claimed tens of thousands of lives and displaced over 13 million people.

The Sudanese foreign ministry pointed to concrete evidence, stating that Kenyan-labelled arms and ammunition were discovered last month in RSF weapon caches in Khartoum. It described Kenya as “one of the main conduits” for Emirati military supplies to what it calls a “terrorist RSF militia,” a charge that, if substantiated, could deepen diplomatic tensions in the region.

The war in Sudan erupted in April 2023 as a power struggle between two former allies: army chief General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and his ex-deputy, RSF commander Mohamed Hamdan Daglo, known as Hemedti.

What began as a rift within Sudan’s transitional government—set up after the 2019 overthrow of dictator Omar al-Bashir—has spiralled into a full-scale conflict, leaving the country in tatters. Entire communities have been uprooted, cities reduced to rubble, and the economy pushed to the edge of collapse.

Amid the chaos, both the army and the RSF have traded accusations of receiving arms from foreign powers, naming countries such as the UAE, Egypt, Iran, Turkey, and Russia as backers of one side or the other.

This international dimension has made the war harder to resolve, with external players accused of prolonging the violence. Sudan’s claim against Kenya is not a vague allegation but one rooted in specific findings and longstanding frustrations. The discovery of Kenyan-marked weapons in RSF stockpiles in Khartoum offers a tangible basis for the accusation, though details about the type or quantity of these arms remain unclear.

The Sudanese foreign ministry has framed Kenya’s alleged role as part of a broader pattern of UAE support for the RSF, asserting that Nairobi has facilitated the flow of military supplies to the paramilitary group. This charge builds on Sudan’s irritation with Kenya’s willingness to host RSF leaders, a sore point that came to a head in late February when the RSF and its allies signed a charter in Nairobi to establish a rival government. Furious at what it saw as Kenya siding with its enemies, Sudan’s army-backed leadership responded by slapping a ban on imports from the East African nation, a move that signalled a sharp deterioration in bilateral ties.

The accusation against Kenya is closely tied to Sudan’s broader grievances with the UAE, which it has long blamed for arming the RSF through neighbouring Chad and Libya. In March, Sudan cut diplomatic ties with the UAE, labelling it an “aggressor state” and accusing it of using the RSF as a proxy to destabilise the country and seize its natural resources, including a foothold on the Red Sea. Abu Dhabi has steadfastly rejected these claims, calling them unfounded despite a growing body of reports from UN experts, US lawmakers, and international organisations suggesting otherwise. Sudan’s foreign ministry has gone further in its case against Kenya, claiming that Nairobi effectively acknowledged its role in the arms pipeline.

It cited a now-deleted post on X by Kenyan government spokesman Isaac Mwaura on 16 June, which read: “Egypt and Iran back (the Sudanese Armed Forces); the UAE backs RSF.” Sudan interpreted this as an admission of Kenya’s complicity, though the post’s swift removal raises questions about whether it was a deliberate statement or a diplomatic misstep. The war’s international entanglements extend beyond the UAE and Kenya. Egypt has been a steady supporter of Sudan’s army, offering both military and diplomatic backing, while Turkey, Iran, and Russia have strengthened their ties with the army-backed government since the conflict began, providing political support and, in some cases, weapons.

The RSF, meanwhile, is widely believed to depend on UAE-supplied arms channelled through regional intermediaries. United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres has spoken out repeatedly about this meddling, warning that “outside powers are fuelling the fire” and urging an end to foreign arms deliveries to both sides. His statements have stopped short of naming specific nations, leaving the issue cloaked in diplomatic caution even as the evidence of external involvement mounts. On the ground, the fighting between the army and the RSF rages on with no end in sight.

The UAE’s alleged role in arming the RSF has been a persistent point of contention, with Sudan accusing Abu Dhabi of funnelling weapons through neighbouring countries like Chad and Libya. Reports from UN experts, US lawmakers, and international organisations have lent credibility to these claims, pointing to a pattern of UAE support for the RSF that includes arms shipments, drone training, and even the recruitment of mercenaries. Sudan escalated its accusations in March 2025, filing a case at the International Court of Justice (ICJ), alleging UAE complicity in genocide against the Masalit community in West Darfur through its military, financial, and political backing of the RSF.

The ICJ dismissed the case, citing the UAE’s exemption from Article 9 of the Genocide Convention, but the filing drew global attention to Abu Dhabi’s actions. The UAE, represented by officials like Ambassador Ameirah Alhefeiti and Assistant Minister Salem Aljaberi, has consistently dismissed these allegations as baseless, framing them as a “cynical publicity stunt” and pointing to its humanitarian contributions, including over $600 million in aid to Sudan since the conflict began.Sudan’s war is not a purely domestic struggle but a conflict shaped by foreign powers with competing interests. The UAE’s involvement is driven by a strategic agenda that blends economic gain with geopolitical influence. Sudan, rich in gold, agricultural land, and a strategic Red Sea coastline, is a key piece in the UAE’s broader ambitions in Africa and the Middle East. Since 2015, the UAE has recruited Sudanese fighters, primarily from the RSF, for its war in Yemen, forging ties with Hemedti that deepened after the 2019 ouster of Sudan’s longtime dictator, Omar al-Bashir.

The UAE, alongside Saudi Arabia, initially supported Sudan’s Transitional Military Council with $3 billion in aid, a move that bolstered military figures over civilian leaders and undermined the democratic transition sparked by the 2019 revolution. As the war broke out in 2023, the UAE reportedly shifted its focus to the RSF, establishing logistical networks through Libya, Chad, Central African Republic, South Sudan, and Uganda to supply weapons, often disguised as humanitarian aid.The UAE’s economic stake in Sudan is substantial, particularly in the gold trade. As the world’s top buyer of Sudanese gold, the UAE imported an estimated 60 tons in 2022, much of it smuggled through intermediaries like Chad, Egypt, and Uganda, according to UN trade data.

A 2023 US State Department advisory noted that the UAE receives “nearly all” of Sudan’s gold exports, with a Swiss NGO, Swissaid, estimating that 405 tons of illicit African gold reached the UAE in 2022. This trade, often facilitated by shell companies and linked to RSF-controlled mining operations, provides financial lifelines to the paramilitary group, enabling it to fund weapons purchases, salaries, and political lobbying. The UAE’s interests also extend to agriculture, with Emirati firms like International Holding Company and Jenaan farming over 50,000 hectares in Sudan, and a 2022 deal with the DAL group to develop an additional 162,000 hectares. A proposed $6 billion port project at Abu Amama on Sudan’s Red Sea coast, intended to link agricultural areas to export terminals, was a cornerstone of the UAE’s maritime strategy but was cancelled by Sudan in 2025 amid accusations of Emirati aggression.

Geopolitically, the UAE’s support for the RSF aligns with its goal of curbing democratic movements and countering political Islam, particularly the Muslim Brotherhood, which it views as a threat. The RSF’s willingness to suppress such movements contrasts with the SAF’s historical ties to Bashir’s Islamist regime, making Hemedti a strategic ally for Abu Dhabi. This stance also pits the UAE against Saudi Arabia, which backs the SAF to secure its influence along the Red Sea corridor, and Egypt, a longtime SAF supporter wary of the RSF’s rise. The UAE’s actions mirror its interventions in Libya and Ethiopia, where it has backed paramilitary groups to expand its influence, often through gold smuggling and economic ventures.

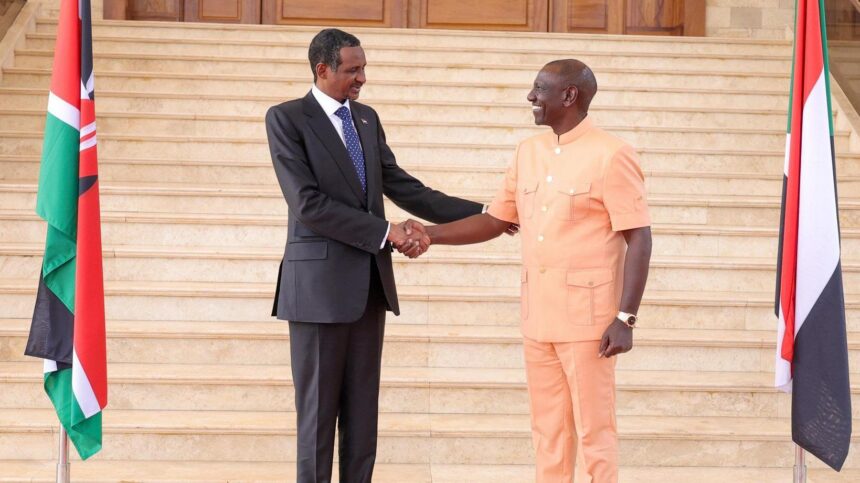

Kenya’s alleged role as a conduit for UAE weapons remains contentious. Analysts have suggested that Kenya’s stance may have shifted following President William Ruto’s January 2025 visit to the UAE, where economic agreements were signed. The discovery of Kenyan-labelled arms in RSF caches could indicate logistical involvement, possibly through regional smuggling networks, though direct evidence of Kenya’s complicity is sparse. The now-deleted post by Mwaura, while damaging, may reflect internal miscommunication rather than official policy. Kenya’s hosting of RSF leaders and the Nairobi charter signing have nonetheless strained relations with Sudan, which sees these actions as enabling a rival faction.

The international response to the UAE’s role has been inconsistent. UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres has called for an end to foreign arms deliveries without naming culprits, while a January 2025 UN report found accusations of UAE support for the RSF credible. US lawmakers, including Representative Sara Jacobs and Senator Marco Rubio, have been vocal, with Jacobs reintroducing the US Engagement in Sudanese Peace Act to sanction those perpetrating genocide and Rubio accusing the UAE of turning Sudan’s war into a proxy conflict. Yet, Western governments, particularly the US and UK, have been cautious, wary of jeopardising the UAE’s strategic importance as a counterweight to Iran and its economic clout. The Trump administration’s warm engagement with the UAE, including $200 billion in deals announced during a 2025 Gulf tour, has overshadowed Sudan’s plight, even as the US imposed sanctions on both the RSF and SAF for genocide and chemical weapons use, respectively. Even though the UAE have pledged to stop arming the RSF, the flow of weapons appears to continue unabated.

The UAE’s narrative of neutrality, bolstered by its humanitarian aid pledges and calls for a ceasefire, contrasts sharply with the evidence of its military support. A leaked UN report from November 2024 documented “multiple” UAE cargo flights to Chad’s Amdjarass airport, a hub for arms smuggling to RSF strongholds in Darfur. Amnesty International’s May 2025 report further detailed RSF use of Chinese-made GB50A guided bombs and 155mm AH-4 howitzers, noting the UAE as the only known buyer of the latter. The UAE’s dismissal of these reports as “baseless” has done little to quell criticism, with groups like Human Rights Watch and the Raoul Wallenberg Centre advocating for legal action at the International Criminal Court or European courts.

Sudan’s war, far from a contained conflict, is a battleground for regional and global powers. Egypt, Turkey, Iran, and Russia back the SAF, with Cairo supplying Bayraktar TB2 drones and Russia eyeing a Red Sea naval base. The RSF, meanwhile, has leveraged UAE support and ties with Russia’s Wagner Group (now Africa Corps) to sustain its operations. The illicit gold trade, intertwined with weapons flows, has enriched both sides, with the UAE as the primary beneficiary. Calls for tougher sanctions on Emirati firms, independent monitoring of gold markets, and pressure on the UAE’s “sportswashing” investments in global sports have gained traction but face resistance due to Abu Dhabi’s diplomatic leverage.

The army has clawed back control of parts of Khartoum and other urban centres, while the RSF holds sway in areas like Darfur. The conflict has shattered Sudan’s infrastructure, paralysed its economy, and left millions reliant on humanitarian aid that is often blocked or insufficient. The influx of foreign weapons has only deepened the crisis, arming both sides for a prolonged struggle that shows little prospect of resolution.